Purity Defines a Substance’s Chemical Identity?

Purity stands as a cornerstone concept in chemistry, fundamentally defining a substance’s chemical identity and properties. When we speak of a pure substance in chemical terms, we refer to matter that possesses a definite and constant composition containing only one type of element or compound with distinct physical and chemical properties. The concept of purity extends far beyond simple cleanliness—it represents the essential characteristic that determines how a substance will behave in chemical reactions and interact with other substances. Why does purity matter so much in chemistry? Because even minute impurities can dramatically alter a substance’s melting point, boiling point, reactivity, and biological activity, sometimes with dangerous consequences.

The pursuit of pure substances has driven scientific advancement for centuries, from alchemists seeking pure elements to modern pharmaceutical companies developing 99.9% pure medications. In our daily lives, we encounter the importance of purity in everything from the gasoline that powers our vehicles to the drinking water that sustains our health. The identity of any chemical substance—whether it’s common table salt or a complex pharmaceutical compound—is intrinsically tied to its degree of purity. Understanding this relationship provides the foundation for all chemical manufacturing, analysis, and research.

Defining Purity in Chemical Terms

In chemical terminology, a pure substance consists of a single type of particle—either atoms, molecules, or formula units—with consistent composition throughout. This definition encompasses both elements, which contain only one type of atom, and compounds, which contain two or more different elements chemically bonded in fixed proportions. What distinguishes a pure substance from a mixture? A pure substance cannot be separated into other substances by physical means, while mixtures can be separated through methods like filtration or distillation because they contain multiple substances physically combined.

The concept of chemical purity operates on a spectrum rather than an absolute state. Even the purest laboratory chemicals contain trace amounts of impurities, though these may be undetectable by standard analytical methods. The acceptable level of purity depends on the substance’s intended use—electronic-grade silicon for computer chips requires far greater purity than silicon used in construction materials. Chemical identity emerges from this precise atomic and molecular arrangement, where even isomeric compounds with identical molecular formulas but different structural arrangements qualify as distinct pure substances with different chemical and physical properties.

Elements: The Purest Form of Matter

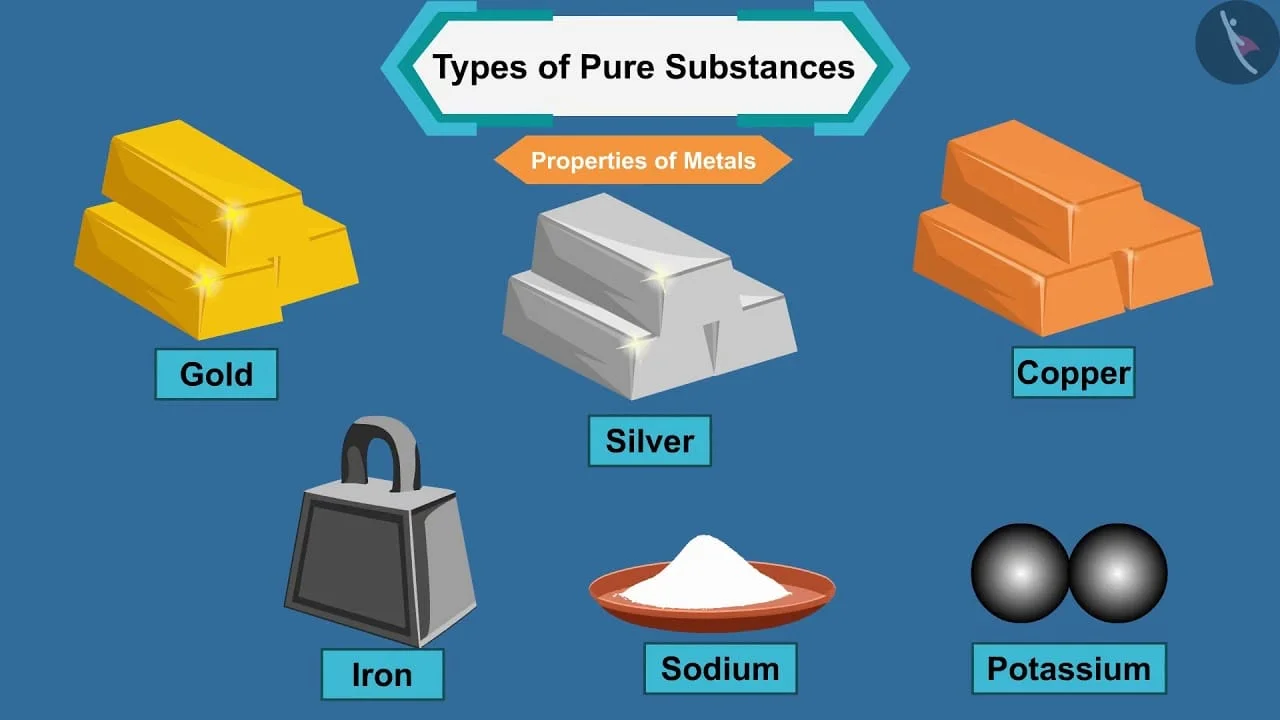

Elements represent the simplest form of pure substances, consisting of only one type of atom characterized by a specific number of protons in its nucleus. The Periodic Table organizes these fundamental building blocks of matter according to their atomic structure and chemical behavior. Each element possesses unique physical and chemical properties that define its identity—mercury’s liquid state at room temperature, carbon’s ability to form multiple bonds, and gold’s resistance to oxidation all stem from their atomic structure. How do we obtain pure elements? Through various purification techniques including electrolysis, fractional distillation, and zone refining, each designed to separate desired elements from naturally occurring mixtures and compounds.

The purity of an element significantly impacts its properties and applications. Ultra-pure silicon (99.9999999% pure) enables the semiconductor industry to create efficient microchips, while less pure silicon finds use in solar panels and alloys. Similarly, the difference between iron that rusts easily and stainless steel lies in the presence of other elements as either unwanted impurities or intentional additives. The quest for pure elements has driven technological progress, from the ancient discovery of how to purify metals like copper and gold to modern techniques that produce ultra-pure materials for advanced technologies. In each case, the element’s chemical identity remains tied to its atomic structure, but its practical identity depends heavily on its purity level.

Compounds: Pure Substances with Fixed Composition

Chemical compounds represent another category of pure substances formed when two or more different elements chemically bond in fixed, definite proportions. This constant composition gives each compound a unique chemical identity with properties often radically different from its constituent elements. Common table salt (sodium chloride), for instance, bears no resemblance to the reactive metal sodium and poisonous chlorine gas from which it forms. What law governs the composition of pure compounds? The Law of Definite Proportions states that a pure chemical compound always contains the same elements in the same proportion by mass, regardless of its source or method of preparation.

The purity of a compound proves crucial to its behavior and functionality. Pharmaceutical compounds provide a compelling example—the biological activity of medications depends critically on their molecular structure and purity. A drug molecule with even slight impurities or structural variations may prove ineffective or cause harmful side effects. This principle extends to all chemical compounds, from the sucrose we use as sweetener to the polymers that comprise plastics. In each case, the compound’s identity emerges from the specific arrangement of atoms and the bonds between them, while its practical utility often depends on achieving sufficient purity for the intended application.

Mixtures and the Challenge of Separation

Mixtures consist of two or more different substances physically combined without chemical bonding between components. Unlike pure substances, mixtures exhibit variable composition and can be separated into their components using physical methods based on differences in properties like particle size, boiling point, or solubility. How do mixtures differ from pure substances in terms of properties? While pure substances have sharp, constant melting and boiling points, mixtures typically melt and boil over a range of temperatures, providing a practical method for assessing purity.

The process of separating mixtures to obtain pure substances represents a fundamental chemical challenge addressed through various techniques. Filtration separates solids from liquids, distillation exploits differences in volatility, chromatography separates substances based on differential partitioning between mobile and stationary phases, and crystallization purifies solids based on differential solubility. Each method aims to isolate individual components from complex mixtures, whether separating crude oil into useful fractions or purifying a synthetic reaction product. The effectiveness of these separation techniques directly determines the achievable purity of the resulting substances, which in turn defines their chemical identity and suitability for specific applications.

Analytical Methods for Assessing Purity

Determining chemical purity requires sophisticated analytical techniques that can detect and quantify impurities at increasingly minute levels. Chromatographic methods, including gas chromatography (GC) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), separate components of a mixture to identify and measure impurities. Spectroscopic techniques like nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and mass spectrometry provide structural information that confirms identity and detects foreign substances. What physical properties help assess purity? Melting point, boiling point, and density provide classic methods for purity assessment—deviations from literature values indicate the presence of impurities.

The standards for purity assessment have evolved dramatically with technological advancement. Where early chemists relied on observable properties like color, odor, and crystal form, modern analytical chemistry can detect impurities at parts-per-billion or even parts-per-trillion levels. This increased sensitivity has redefined what constitutes a “pure” substance for different applications. Pharmaceutical standards might require 99.5% purity for a drug substance, while electronic materials may need 99.999% purity or higher. In each case, analytical methods provide the quantitative data needed to verify that a substance’s composition matches its purported chemical identity and meets the necessary specifications for its intended use.

The Economic and Practical Implications of Purity

The economic value of chemical substances often correlates directly with their purity level. Industrial-grade chemicals command lower prices than laboratory-grade or pharmaceutical-grade equivalents due to their higher impurity content. This economic reality drives extensive purification processes across industries, from petroleum refining to pharmaceutical manufacturing. How does purity affect manufacturing costs? Achieving higher purity typically requires more sophisticated equipment, additional processing steps, and rigorous quality control, all increasing production costs that must be balanced against the product’s performance requirements.

The practical implications of chemical purity extend throughout modern society. In agriculture, fertilizer purity affects crop yields and environmental impact. In healthcare, drug purity determines therapeutic efficacy and patient safety. In manufacturing, material purity influences product quality and reliability. The water we drink, the food we consume, and the fuels that power transportation all undergo purification processes to ensure they meet standards appropriate for their use. In each context, the substance’s functional identity—what it does and how it performs—depends fundamentally on its chemical purity, creating continuous demand for improved purification technologies and more sensitive analytical methods.

Table: Purity Standards Across Industries

| Industry | Typical Purity Requirement | Key Impurities of Concern | Consequences of Impurity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical | 99.0-99.9% | Isomers, byproducts, residues | Reduced efficacy, toxicity, side effects |

| Electronic | 99.999-99.9999999% | Metal ions, particulates | Device failure, reduced performance |

| Food Grade | 95-99% | Toxins, allergens, contaminants | Health hazards, spoilage, off-flavors |

| Laboratory Reagents | 98-99.9% | Water, reaction intermediates | Experimental error, side reactions |

| Industrial Chemicals | 90-99% | Starting materials, catalysts | Process variability, product defects |

Purity in Pharmaceutical and Medical Applications

Nowhere is chemical purity more critical than in pharmaceutical applications, where impurities can transform life-saving medications into harmful substances. The identity, strength, quality, and purity of drug substances are rigorously regulated worldwide, with manufacturers required to demonstrate comprehensive control over their production processes. Why are pharmaceuticals subject to such strict purity standards? Because biological systems exhibit exquisite sensitivity to molecular structure, where even stereoisomers—molecules with identical atomic connectivity but different spatial arrangement—can have dramatically different pharmacological effects.

The tragic historical example of thalidomide, where one enantiomer provided therapeutic benefit while the other caused birth defects, underscores the critical importance of chemical purity and molecular identity in pharmaceuticals. Modern drug development includes extensive characterization of potential impurities that may form during synthesis or storage, with strict limits established for each. Analytical method development focuses on detecting and quantifying these impurities at increasingly lower thresholds. The pharmaceutical industry’s commitment to purity extends beyond active ingredients to excipients, solvents, and packaging materials—all potentially contributing impurities that could compromise drug safety, stability, or efficacy.

Environmental and Biological Perspectives on Purity

In environmental contexts, the concept of purity takes on different dimensions, focusing on the absence of pollutants and contaminants rather than the presence of a single chemical species. Air and water quality standards establish maximum allowable concentrations of various impurities based on their environmental and health impacts. How do natural systems handle chemical purity? Biological organisms have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to selectively absorb, exclude, or transform chemical substances, maintaining the precise internal composition necessary for life despite variable external conditions.

The biological perspective reveals that absolute purity rarely exists in natural systems. Organisms constantly manage complex mixtures of substances, employing selective barriers, transport systems, and metabolic pathways to maintain homeostasis. This biological reality doesn’t diminish the importance of chemical purity but rather contextualizes it—while laboratory chemistry often seeks to isolate pure substances, biological systems excel at managing complex mixtures. Understanding this balance helps explain why some synthetic chemicals prove problematic in the environment—their identity and persistence may disrupt evolved biological processes that manage naturally occurring substances.

The Philosophical and Theoretical Dimensions of Purity

The concept of chemical purity carries philosophical dimensions that extend beyond practical applications. The very idea that substances have essential identities tied to their composition represents a fundamental premise of modern chemistry. This perspective has evolved from ancient philosophical concepts of essential natures to contemporary understanding based on atomic and molecular structure. Is absolute purity attainable? Theoretical considerations and practical experience suggest that absolute purity represents an ideal limit that can be approached but never fully reached, as analytical methods continually improve to detect ever-smaller quantities of impurities.

This theoretical understanding informs how chemists think about matter and its transformations. The identity of a chemical substance resides in its molecular structure, but its practical manifestation always involves some level of impurities. This reality doesn’t undermine the concept of chemical identity but rather emphasizes that substances exist along a spectrum of purity with practical consequences. The philosophical tension between idealized pure substances and the reality of complex mixtures enriches chemical thinking, encouraging both rigorous purification efforts and thoughtful consideration of how substances behave in the imperfect, mixed-state environments where they’re typically used.

Future Directions in Purification Technology

The ongoing pursuit of higher purity standards drives innovation in separation science and analytical chemistry. Emerging technologies like membrane-based separations, advanced chromatographic methods, and specialized crystallization techniques continue to push the boundaries of achievable purity. These developments support progress across sectors, from medicine to electronics to energy production. What future advances might transform our approach to chemical purity? Molecularly selective separation materials, artificial intelligence-optimized purification processes, and increasingly sensitive analytical instruments promise to redefine purity standards in coming decades.

The relationship between purity and chemical identity will continue to evolve as technology advances. Substances previously considered pure may be reclassified as detection methods reveal previously undetectable impurities. At the same time, increasingly pure materials may exhibit novel properties that expand their useful applications. The fundamental connection between composition and identity will remain, but our ability to control, characterize, and utilize that relationship will undoubtedly grow more sophisticated. This ongoing progression ensures that the concept of chemical purity will continue to serve as both a practical necessity and a theoretical foundation for chemical science and its countless applications.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the difference between purity in chemistry versus everyday language?

In chemistry, purity refers to a substance containing only one type of element or compound with constant composition, while in everyday language, purity often means cleanliness or freedom from contamination without the precise chemical definition.

2. How can impurities change a substance’s properties?

Impurities can alter melting and boiling points, change color and reactivity, reduce electrical conductivity, modify strength and hardness in materials, and cause unexpected side reactions in chemical processes.

3. Why do pure substances have sharp melting points while mixtures melt over a range?

Pure substances have uniform molecular interactions that break simultaneously at a specific temperature, while mixtures contain different substances with varied interactions that break at different temperatures, creating a melting range.

4. What is the purest substance ever created?

Silicon crystals for semiconductor applications rank among the purest substances, with impurity levels below 1 part per billion, though exact purity claims depend on measurement capabilities and which impurities are considered.

5. How do chemists express purity quantitatively?

Chemists typically express purity as a percentage by mass (e.g., 99.5% pure) or in terms of specific impurity concentrations (e.g., <0.1% water), often supported by analytical data from multiple techniques.

Keywords: Purity, Chemical Identity, Substance, Element, Compound, Composition, Mixture, Impurity, Atom, Molecule, Chemical Reaction, Oxidation, Periodic Table, Formula Unit, Particle

Tags: #Purity #Chemistry #ChemicalIdentity #Elements #Compounds #ScienceEducation #Laboratory #MaterialsScience #Pharmaceuticals #QualityControl